Day 2

1. From nucleotides to DNA

In the last post we saw that nucleotides are the building blocks of DNA and RNA, and are constituted by:

- A pentose sugar (ribose or deoxyribose)

- A nucleobase (purine - A and G - or pyrimidine - C, T and U)

- One or more phosphate groups

Nucleotides can generate new structures by bonding (1) "vertically" or (2) "horizontally":

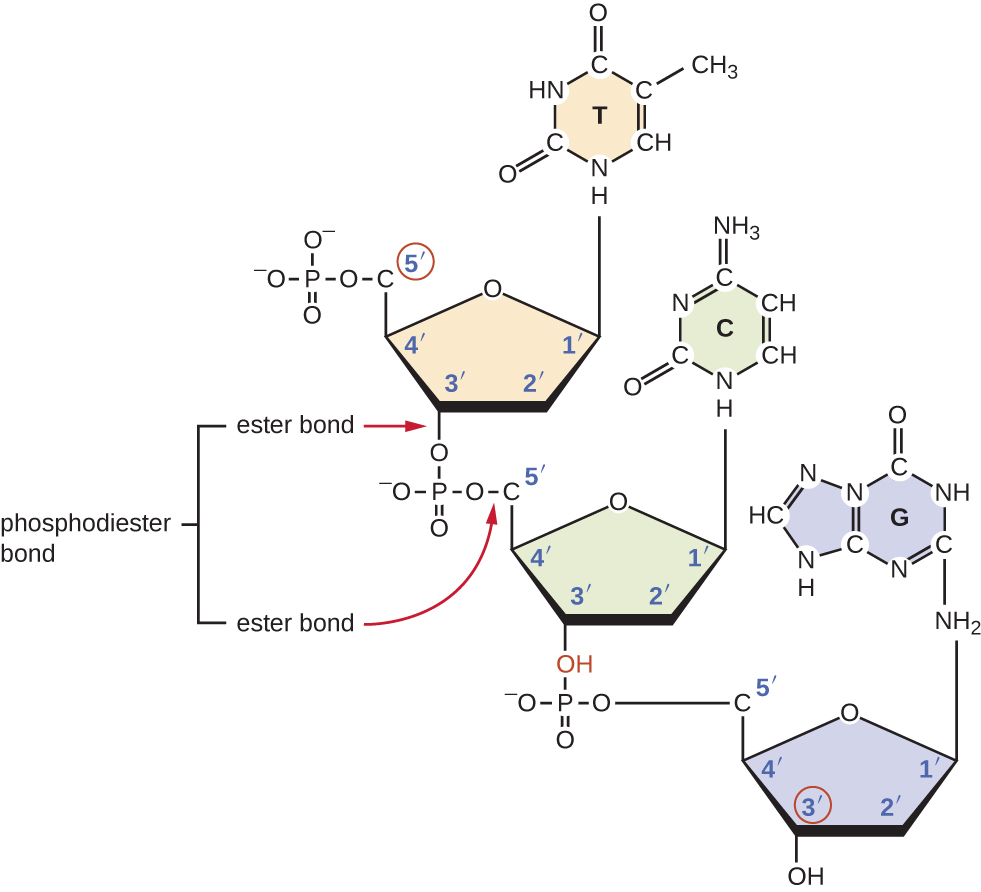

- Two nucleotides form a dinucleotide through a phosphodiester bond, which comes from a highly hexoergonic condensation reaction between a nucleoside-tri-phosphate (NTP or dNTP) and the 3' hydroxil of the pentose sugar of a nucleoside-mono-phosphate. The (d)NTP frees two of its three phosphate groups (and the related energy) to form a highly stable covalent bond with the 3' carbon.

- Two nucleotides form a base pair (bp) by cnnecting their nucleobases via H-bonds. H bonds are not as strong as covalent bonds, but their are the strongest among the weak bonds: they occur between a highly electronegative atom (O, N, S) and a hydrogen atom, and the strength of hydrogen bonds relies in their quantity. A single molecule of human DNA contains billions of hydrogen bonds, hence its great stability.

Regarding point 2, we have to add two important details:

- Nucleobases do not associate freely, they follow a precise rule, known as complementarity: A only associates with T (or with U), and C only bonds with G. The first to observe complementarity was the American biochemist Erwin Chargaff, who formulated the two Chargaff's rules

- In light of what mentioned in the previous point, we observe a difference in how many H-bonds are formed: C-G pairs form 3 H-bonds, A-T pairs only two. This difference is key in determining the stability of a DNA sequence, as AT-rich DNA regions are more unstable than GC-rich ones. This also hints at the function of the regions: given the difference in stability, more stable (GC-rich) regions are mostly gene-coding, whereas AT-rich regions are generally repeated/spacer/anchoring/promoter/enhancer... sequences

So, if we stick more than two nucleotides together vertically, and we pair them with a complementary strand horizontally, we have completed our first nucleic acid molecule!

We can notice two very important things here:

- There are always a 5' carbon with a free phosphate group and a 3' carbon with a free hydroxil group (they are known as the 5' and 3' end)

- There are two clear portions of the nucleic acid structure: a sugar-phosphate backbone, which is highly polar and thus hydrophilic (that's why it is exposed to the outside, as the cell environment is water-based), while the base pairs are non-polar (thanks to the H-bond stabilization), thus hydrophobic (and that's why they are on the inside). But things are not as simple as they seem: there are, indeed, more rules to "make" a DNA molecule :)

2. The DNA structure

As we know, DNA is a double helix. This means that:

- There are two strands in the helix. These strands are anti-parallel, which means that they are parallel to each other but oriented in a different way: there's a 5'-3' strand and a 3'-5' strand

- The two strands spiral following two grooves of unequal dimension: the major and the minor groove. The spiraling is generally dextrorotatory.

- DNA strands has to balance the repulsive forces among negative charges along the sugar-phosphate backbone with several adjustments, as the internal H-bonds are not really sufficint in most of the cases. The bases are then stacked not in a perfectly parallel fashion, but they can rotate along the helix axis (twist, or repulsion among two base pairs), along the pairing axis (tilt, rotation in the positioning of two nucleotides within a base pair) and along the sugar-phosphate backbone (roll, or repulsion between two nucleotides within a dinucleotide)

The key take-home message here is that DNA strands are never perfectly aligned and parallel, but there are always twists, tilts and rolls to adjust the DNA structure in order to minimize instability.

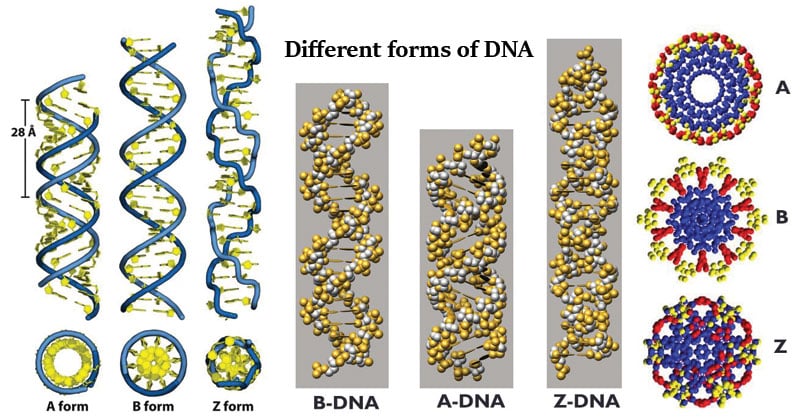

We recognize three primary DNA structures:

- B, the most widespread, is considered the "normal" structure that DNA takes on when it is exposed to normal conditions. The diameter of the helix is 10 A, and each step (360° rotation of the helix) takes 34 A of vertical distance, with 11 bp stacked in there.

- A, this structure is "short and thick", often associated with extreme conditions such as dehydration and cold. It is also frequent in double stranded RNAs and in DNA-RNA hybrids

- Z, this structure is "long and slim",, and there is scarce insight on its function, even if it might be connected with some cancerous processes.

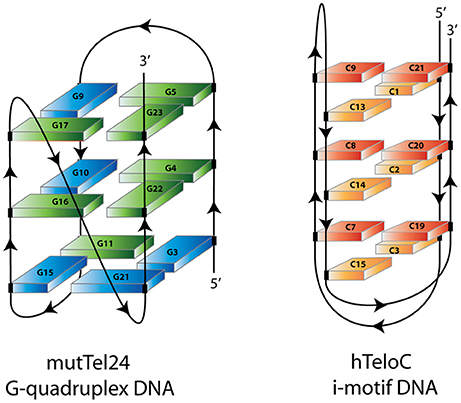

Beyond the primary structures, DNA can also associate in secondary structure due to intra-strand bonds: for example, G-quadruplexes form when 4 complanar Gs bind each other through non-canonical H-bridges, or in C-rich motifs we can have non-canonical bonds among Cs. Non-canonical bonds often determine the so-called "triple helix" motif.

There are also other structures in which DNA strands can associate when there is complementarity within the same strand (often in highly repetitive regions). You can then have a cruciform DNA, where short sequences pair with each other deviating the course of the molecule and constituting a cross-like structure, and a slipped DNA, where larger chunks of the strand are left single-stranded because they are able to pair with themselves.