Day 2

1. Cytoskeleton and Cell Growth

The cytoskeleton plays a crucial role in the plant growth, as it is highly involved in the cell elongation process:

- During the quiescent phase, the cytoskeleton is mainly made up by microtubules casually distributed in the cytosol

- During the active elongation we have a structured, high-level cytoskeleton in which the microtubules are organized in a polarized way way, perpendicular to the direction of growth.

In the interphase, the actin filaments are also laid in a casual way, but they wrap the nucleus and branch out from there to reach other organelles and keep them in place.

Actin filaments also help move things around the cell, like particles and organelles. They are responsible for the so called "cytosolic currents", where they associates with motor proteins like myosin. Myosin is an omodimer, made up by 2 globular heads and 2 coiled-coils tails. The two heads can hydrolize ATP, in a cycle that gives myosin heads motor properties. Myosin interacts with actin filaments, making them slide while the heads reach the "power stroke" phase (see the myosin cross-bridge cycle). This is the way in which things are moved around the plant cell!

Several studies leveraged transgenic lineages of Arabidopsus thaliana, a model organism for plants, mixing the plant myosin with an algal fast-paced myosin or the human slow myosin. The results were not far from expectations:

- The wild-type plants grew normally

- The fast-paced myosin lead to an enhanced and faster growth, with bigger cells on average

- The slow myosin caused a slowing in the growth and smaller cells

2. Plastids

Plastids are key components in the plant cell: they are indeed its metabolic powerhouse, where several functions are carried out (depending on the type of plastid):

- Photosynthesis and photo-biological functions

- Secondary metabolism

- Nutrient or pigments stock

2a. Proplastids

As the name and the TEM images suggest, proplastids are immature precursors of other plastidial organelles, and they generally evolve in a tissue-specific way. Proiplastids are generally small, with only a neonatal version of the structures they will acquire with maturation (e.g. unorganized chlorophyll crystals). Proplastids are typically of quickly-reproducing meristematic cells (the equivalent of animal stem cells): these cells are generally not specialized and, needing to reproduce quickly, they cannot spend to much energy in the formation of mature plastidial structures. By the time meristematic cells reach a full differentiation stage, also the proplastid have matured in specialized plastidial organelles.

2b. Etioplasts

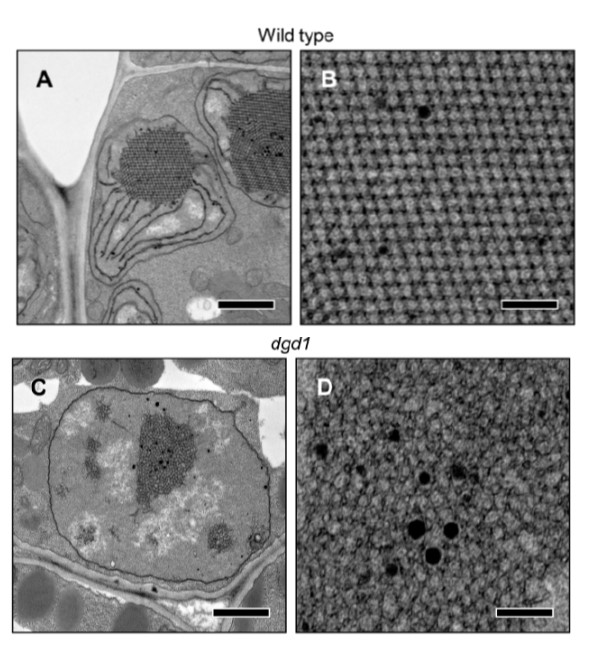

Etioplasts are a semi-mature form of plastids: they develop with the absence of light, and they represent a very good example of energy optimization by the plant cells. Since converting proplastids to chloroplasts requires lots of energy, it is only convenient when there is light and the energy balance can be eventually positive for the plant: if the plant is in the dark, it converts proplastids in production-ready structures, that still are nit deployed. The chlorophyll starts gathering in chrystal-like structures known as lamellar body (center of image A). As soon as light kicks in, the etioplasts are turned into chloroplasts.

2c. Chloroplasts

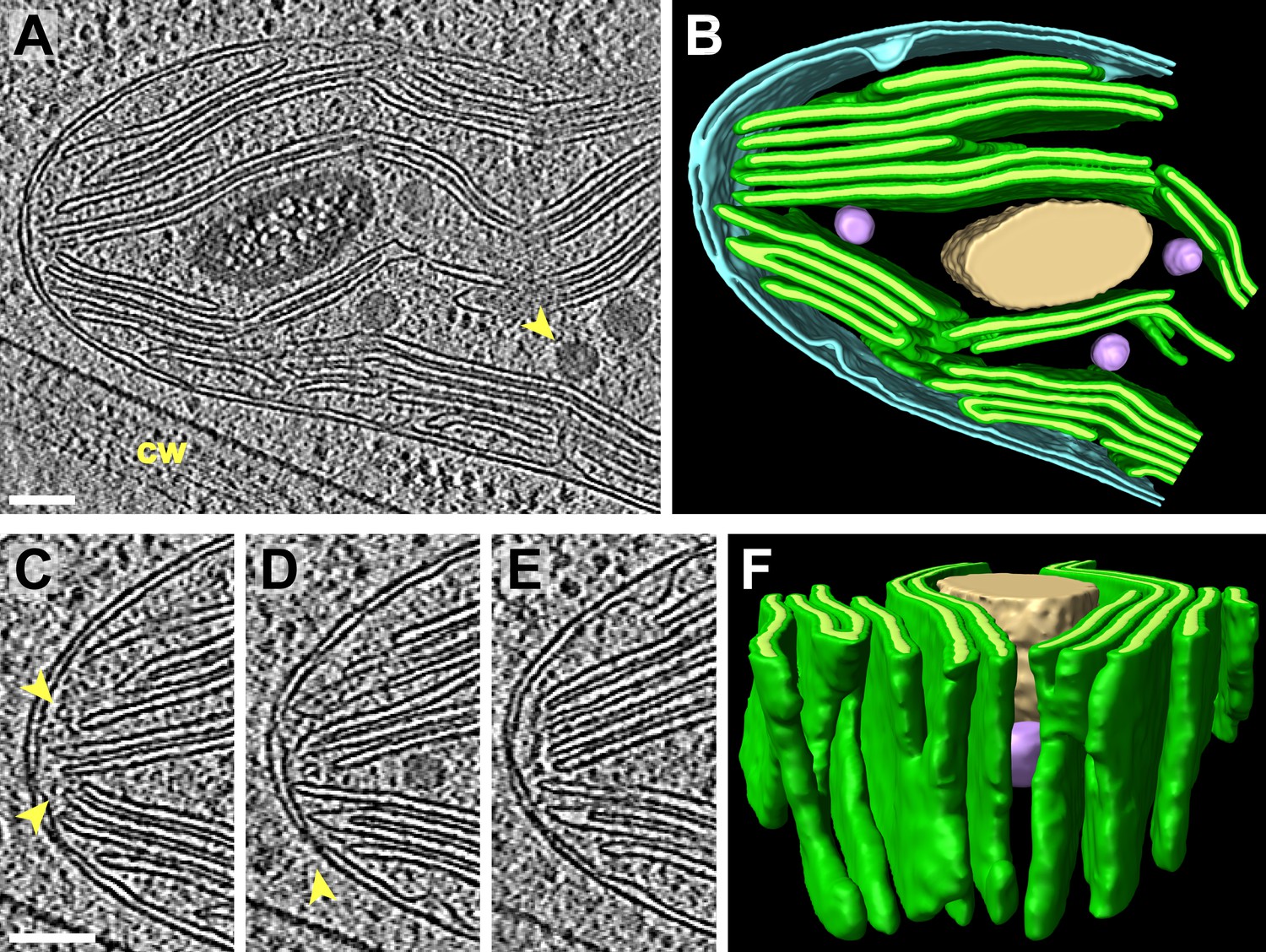

Chloroplasts are the photosynthetic center of the cell: they have internal membranes arranged in a bag-like shape, known as tilacoids, where reaction centers are exposed to light. This bag-like membranes are stacked in piles known as grana. This organelles are highly efficient and specialized, and contain several pigments like chlorophyll, anthocyanins and carotenoids. When the chloroplast "gets old" (senescence process), its internal organization start to degrade, and the chlorophyll is destructured and recycled: this process leaves space for the anthocyanins and the carotenoids (orange-red colors), which explains why leaves turn red/orange/yellow/brown during fall.

2d. Chromoplasts

Chromoplasts contain pigments such as anthocyanins (pink-red), carotenoids (oranfe-yellow-red) and flavonoids (ultraviolet colors): they do not contribute to photosynthesis, but where evolved for different tasks. Colors are indeed crucial in attracting pollinators or refraining predators from eating the plant: plants that where able to exploit colored flowers or fruits had more success throughout the history of life, and that got them selected and produced the wonderful variability of colors in nature. This is part of plant-pollinators co-evolution.

2e. Leukoplasts

Leukoplasts are centers for processing secondary metabolites: they often produce useful molecules in plant-based pharmacology or for actual drugs prepration. Leukoplasts, as the name suggest, lack pigments, keeping a translucid appearence under the microscope. Leukoplast can mature in different nutrient-stocking structures, such as amyloplasts (polysaccharides), elaioplasts (lipids) and proteinoplasts (proteins). Root vegetables, such as tubers, are rich in nutrients-filled plastids.

3. Plastids reproduction

As mithocondria in animal cells, plastids can divide indepemdently from the cellular systems abnd are inherited separately from the other organelles. Their division appears to be dependent on the FtsZ protein, responsible for cellular division in bacteria, which hints at the endosymbiotic theory. Their division is also dependent on Plastid Division proteins (PDV): when PDVs are overexpressed, they speed up plastid division and lead to an increase in the number and decrease in the size of chloroplasts: this is achieved by expressing a strong constitutive (always active) promotor for the operons codifying for PDVs. If, on the other hand, we insert a antisense sequence inside the codifying portion of the operon, we get out the traditional RNA + the antisense sequence, which is its complementary. The RNA and the abti-RNA stick to each other and the complex is rapidly degraded by nucleases: in the so called antisense lineages, we can keep the growth of the plant under control, and we have the production of less but bigger chloroplasts.

Plastid reproduction is influenced by phyto-hormones and cytokines (cellular messengers), highlighting how the process is deeply connected with cellular and plant growth.

When plastids start reproducing, they implement the FtsZ protein, which is an homolog of tubulin in bacteria. When FtsZ is activated, a cascade of signal transduction is initiated: the FtsZ protein activates a protein named ARC6. This protein, in turn, recruits the plastidial division proteins PDV1 and PDV2: these two are key in attracting the final actor in plastidial division, the GTPase DRP5B, similar to dynamin in human neurons.

Plastids are semi-autonomous organelles, meaning that they reproduce and are passed on independently from the main reproductive cycle of the cell. This was firstly noticed when it was discovered that the inheritance of various charachters was non-Mendelian (these charachters were linked to plastids). Plastids have their own genome, the plastome, which is actually circular double-stranded DNA: it's smaller than a normal bacterial genome and contains only 150-200 genes. This is explained by the endosymbiotic theory: the plastid is thought to have been a bacterial alga before being phagocyted (approx. 1.2 billion years ago) by the precursor of the actual plant cell. This has led to a coexistence of the two cells, one within the other, and, in millions of years of evolution, the chloroplast slowly lost all the unnecessary functions (nutritive and defensive mainly), because the plant cell took them on: this lead to a gene loss, and also to a gene transfer from the plastome to the nuclear genome. The plastidial genomes are mainly related to photosynthesis and to transcription/translation of proteins.