Day 4

1. Plant Life Cycle

Plants have two types of growth:

- Determined growth, which usually involves organs that have a final stage of differentiation with a well defined size, such as flowers, fruits or leaves. The number of cells reaches a certain threshold and remains stable from there, while cells can still elongate (elongation growth).

- Non-determined growth, that involves the trunk and the and the roots of the plant. They both have the so-called apical meristem, which promotes their growth indefinitely. The apical meristem of the trunk descends to form the leaves primordia, which help the formation of leaves along with the leaves meristem. On the other hand, in the roots, meristem cells go up to form roots organs such as root hairs.

Meristems can be primary or secondary (although secondary growth is not common to all the plants): the first ones are the apical meristems (Shoot Apical Meristem - or SAM, and Root Apical Meristem - or RAM[^1]), the other ones are known as lateral meristems and promote the volumetric growth of the trunk (only in species belonging to the Gymnospermata taxon).

Primary growth then corresponds to an elongation growth (for the entire organism, not to be mistaken with the cellular elongation growth), whereas the secondary growth is linked to an increase in the diameter of the plant, both in the roots and in the wooden portion of the trunk.

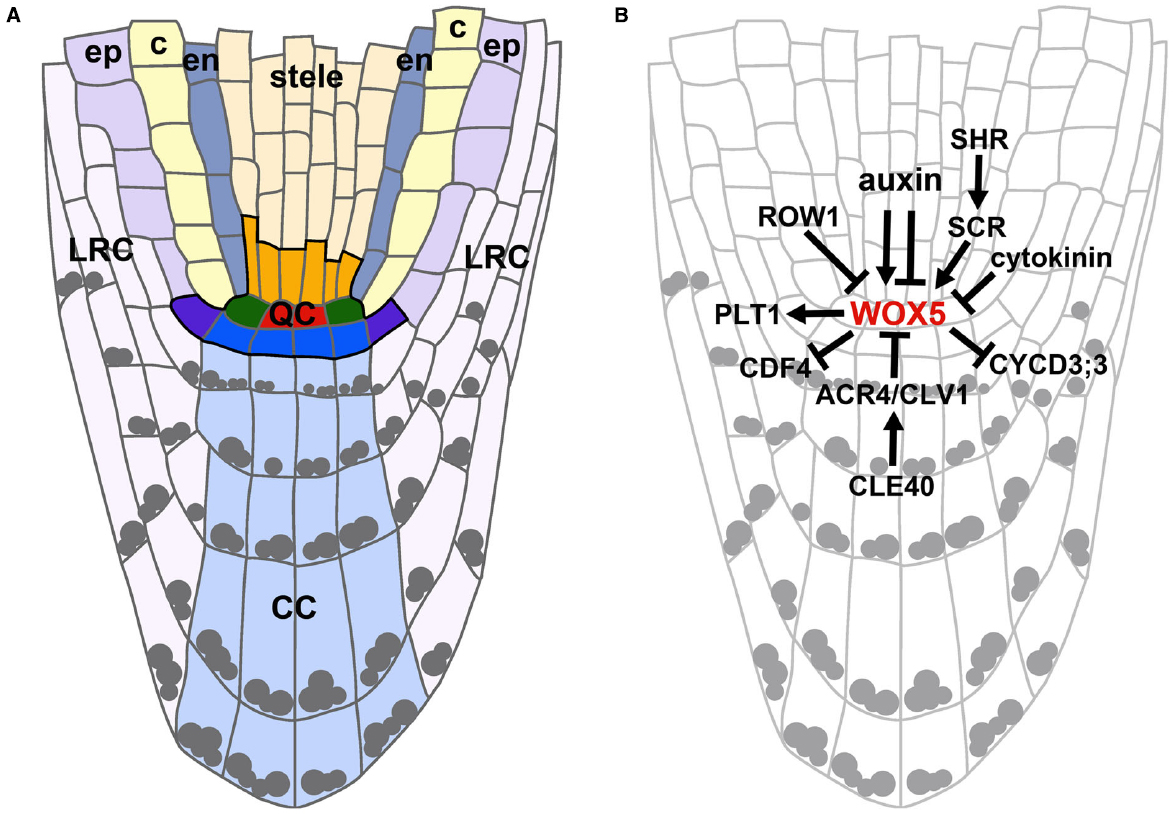

As you can see, there are several regions related to the meristem (here we have the root meristem). There is an organization center, which is layered to set the cells growth in the correct patterns, and the quiescent center, that controls cellular proliferation to avoid cancerous growth.

There is a strong control over the molecular events that occur at the meristems, and the principal effector molecules are phytohormones, i.e. plant hormones: these molecules act as the hormones in the human body: they have a receptor (on the membrane or inside the cell), and the binding of the hormone with the receptor initiates a cascade of signal transduction that has various effect on cell growth, life cycle, metabolism, reproduction... and many more biochemical chains.

Secondary meristems can be of two types:

- Lateral meristems: they are responsible for the volumetric growth of the plant and for the augmentation of the low-quality carbon biomass in Gymnospermata. They generally make the diameter of the trunk grow, accumulating layers of lignin or other wooden-y materials

- Temporary apical meristems: they are employed by some plants in stressful conditions and they are part of the extraordinary plasticity which is exhibited by plant systems. Some examples of conditions influencing the growth of a plant and requiring adaptation can be: extreme (low or high) temperatures, scarcity of water/floods, fires, animals, fertilizers.

2. Arabidopsis thaliana: the model organism

Arabidopsis thaliana is the model organism for terrestrial plants, and that's because:

- It's an annual plant, with a very short life cycle (approx. 6 weeks)

- It produces hundreds of seeds

- It has a very simple genome: 5 chromosomes in the haploid state.

- Two polyploidization events (180 and 112 million years ago)

- Compact number of genes (26.000) with >80% of the genome which is actively transcribed and codifies for gene products.

- Only 17% of the duplicated genes derive from genic amplification events

Arabidopsis thaliana is then way easier to deal with on a genetic point of view then plants like tobacco and mais, which have a small portion (approx. 2%) of the genome which codifies for genes and have way wider genomes (tobacco is 1800 Mbp, mais is 6600 Mbp).

Other biological phenomena (such as nitrogen fixation), cannot be explored with A. thaliana, as the plant does not do them, so we have other model organisms, such as:

- rice for monochotyledons

- tomato and potato for horticultural species

- poplar for wood species, because it has a short life cycle and responds well to in vitro cultivation

3. Totipotency and plasticity of plant cells

Plan cells have an amazing feature: they are totipotent. Totipotency is a very intriguing concept: it means that a cell is so undifferentiated that it can generate an entire organism from scratch. This feature is not unique to plants, as animal cells can also be totipotent, but they are only for a short time, i.e. when they are in the zygote form, prior to the first division: from the blastomer on, animal cells can only be pluripotent at their maximum differentiation power (and there is research to reprogramme differentiated cells into Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells). For plants, things are way different: cells maintain the power to transdifferentiate into totipotent cells also when they are in a completely differentiated stage.

This was discovered by the botanist Gottlieb Haberlandt, that tried stimulating cells from in vitro cultures using different hormonal/molecular cocktails until he managed to reach de-differentiation. He is often regarded as the father of in vitro plant studies.

So, just to clarify the field:

- Differentiation is the sequential process, involving complex molecular mechanisms regulated mostly by hormones and growth factors, with which the cell reaches its final stage

- De-differentiation is the process that the cell enacts to go from a more to a less differentiated form. It generally involves going back to pluripotency

- Plasticity is the phenomenon with which the plant can modulate its metabolism and growth based on the external conditions. It is the direct consequence of plants' sessile life: if they were able to escape stressful situations like animals (that can, generally, move), they would not need fine molecular regulation and adaptation.

NOTE: Making plants grow in vitro has been a long-standing challenge because scientists were not able to find the right nourishment to include in their cellular cultures. Only in 1962 Murashige and Skoog came up with the MS terrain , an effective solutions to grow most of the plant cells in vitro.

3a. De-differentiation

De-differentiation is a process often carried on in vitro starting from a small piece of leaf tissue: this process generally follows stressful environmental cues, such as the mechanical laceration which cells are exposed to when taken away from the leave. Also living in a cell culture for a long time can bring about oxidative stress. If the cells start to de-differentiate, we will see microscopic callous formations in some days and then macroscopic ones. The callous can then take three paths:

- Cell cycle: cells start to reproduce fast and they grow in even bigger structures

- Cellular death: the stress from the environment was beyond repair, so it's more economic not to invest energy in repair.

- De-differentiation: cells take on a new differentiated function, or they go back at being what they were before.

De-differentiation involves basically all plant cells, with few exceptions such as highly lignified tracheids.

The genetic basis of De-differentiation is known as genetic re-programming, and it is basically a pattern of variations in gene expression, organized by positive and negative regulator molecules from inside and outside the cell. This re-programming can "bring back to life" also transposons, mobile elements in the genome that can "jump" into several positions and break/activate the transcription of the linked genes.

Genetic re-programming is really cool, but it also makes it impossible to have a universal protocol for de-differentiation in all plant tissues, because it switches on and off different genes patterns in different tissues.

The callous that forms from the de-differentiation process can be of two kinds:

- non-organ bearing: essentially a mass of cells without a specific form. It can be friable or compact.

- organ bearing: this callous presents organogenesis, i.e. formation of organs. This can happen even without a growth-supporting nourishing substrate. In embryonal callouses we can then see buds, primordia of leaves and roots.

The de-differentiation process is often used as a starting point in the workflow that generates GMOs: starting from the de-differentiated cells, we perform several genetic modifications to improve qualities that are of interest to us.

[^1]: Please note that the term RAM is generally not used to indicate the Root Apical Meristem, but rather Random Access Memory: so no, computers do not have root apical meristems.